The best-selling expose she wrote on the subject, “The American Way of Death,” skewered the funeral industry for its gross materialism and was hailed as a landmark in investigative journalism that led to the Federal Trade Commission enacting new legislation regulating industry practices.

Mitford would be thrilled with plans by the Essex County Greenbelt Association to promote local dialogue on “green, or natural burials” in response to what Mary Williamson, who is director of development and community engagements for the Greenbelt, calls “growing community interest … in exploring the implications of green burials for land conservation.”

That dialogue, with Candace Currie, of Green Burial Massachusetts and the Mount Auburn Cemetery, will take place this Thursday, March 17, at Sawyer Free Library, following a free 6 p.m. screening of the award-winning documentary, “A Will for the Woods.”

Williamson, who organized the event, which falls on St. Patrick’s Day, swears that any connection between green burials and the wearing of the green was an unintended, if ironic, coincidence. That said, the Irish are famous for their reverence for the dead, and “green graveyards” are a growing trend on the Emerald Isle, while across the Irish Sea in the United Kingdom there are more than 340 established natural burial grounds (NBGs).

‘Self-composting’

Jeremy Kaplan, cinematographer and one of four co-directors on the American-Australian filmmaking team, will introduce the one-hour advocacy documentary, which draws the viewer into a “life-affirming portrait of people embracing timeless natural cycles” through the narrative of Clark Wang, a young musician, folk dancer and psychiatrist who, while dying of lymphoma, becomes passionate about green burials and determined to make a gift of himself back to the planet.

Nobody wants to die, let alone be buried, including Wang. And that, says Williamson, “is one of the things that makes the film so thought-provoking.” In his seven-year battle against cancer, Wang left no stone unhurled against the disease that was killing him. He wanted to live so much, he says, that it was the thought of living on through the ecosystem that sustained him.

Wang’s presence in the film — as a living, loving, joyful, humorous and brave being — makes the concept he is unabashedly selling (in his words, “self-composting,”) palatable to audiences long used to “The American Way of Death.”

The concept of green burials is actually neither new nor the reserve of extreme environmentalists. Mainstream media analysts attribute its sudden growth spurt in the United States to the HBO series “Six Feet Under” (2001 to 2005) which explored the trend amid heightened audience awareness of environmental concerns. There are now about 40 certified green burial grounds nationwide and a “natural death care” industry, which advocates — including religious communities and clerics — see as an extension of end-of-life palliative care, and a return to ancient sacred rituals.

Just as Clark Wang is a great salesman, the film itself is a great sales vehicle. Beautifully shot and edited, it’s had wide theater release in the United States and Canada, swept awards at nine film festivals, aired on PBS, been hailed by TED as “a must-see documentary,” and praised by Discovery News as “a film that has hit a cultural nerve.”

Going green

Green or natural burial may not be something you want to think about, but this film will make you “think out of the box,” as green burial advocates are fond of saying.

Williamson, who admits to being initially squeamish about the subject when first approached by local advocates, asks that you “bring an open mind,” and says one thing that won her over was realizing “the incredible amount of materials that are put into the earth that won’t decompose.”

An estimated 60,000 tons of steel and 4.8 million gallons of embalming fluid are put into American soil each year through the $20 billion a year American funeral industry. Green burials, by contrast, lay the deceased to rest in the earth in biodegradable materials.

“Shrouds speed up decomposition and reunion with the land,” says Williamson. Other materials run the gamut from a bed of wood chips to wicker basketry to simple, biodegradable pine caskets.

The funeral industry is adapting traditional practices to accommodate the green burial movement, and a growing number of cemeteries, including Cambridge’s historic Mount Auburn Cemetery, now provide “options” for green burials.

‘Lots of interest’

But, says Williamson, local interest in green burials centers on the creation of a dedicated land preserve that would provide an option to traditional cemeteries. “There’s so much to learn,” she says, “so we’ve organized a group. There are so many aspects, we feel we need an expert partner to help us make sure we’re doing things right. We may find that it won’t work for us. But it was instigated by members of the community and there’s a lot of interest out there.”

The film’s trailer opens with an anonymous voice-over saying, “They don’t call them cemeteries, they call them preserves. ..”

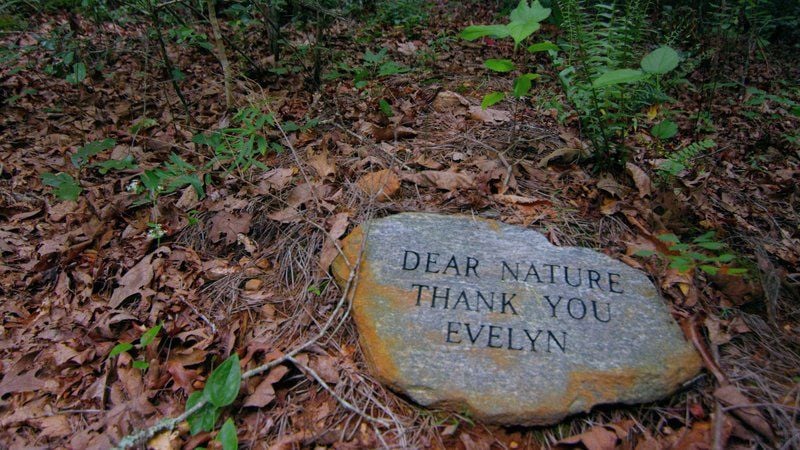

Wang is buried in one such preserve — a green, leafy clearing in a forest in North Carolina that somewhat resembles Dogtown.

Like Dogtown, its grounds are scattered with stones that are carved with words. Only these stones are small, flat and unobtrusive, and instead of carrying commanding instructions on how to live, they suggest how to die with grace and gratitude.

The stone featured in the film’s trailer marks the grave not of Wang, but of a woman called Evelyn, and says simply, “Dear Nature, Thank you.”

Joann Mackenzie may be contacted at 978-675-2707, or at jmackenzie@gloucestertimes.com.